The witches of Hull, East Yorkshire and beyond

GRIM FATE: A 1665 illustration of witches being hanged

The Way it Was

In partnership with Hull History Centre

Halloween is a time for ghosts, ghouls, monsters and witches. Today of course these are fictional characters, but 400 years ago witchcraft was seen as real.

In an age when little about the natural world was understood by science, so much that was uncertain or unknowable was explained with magic. If you, or your child, or your cow fell sick and died, that was as likely as not due to the malign acts of a local witch.

In this latest contribution to The Hull Story, we recount two incidents regarding witches and witchcraft. The first is the execution of men and women in Hull on the charge of witchcraft. The second relates to one of the most infamous witch trials in history. One that again has a local connection – but this time across the Atlantic to Massachusetts and the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

Witches of Hull by Martin Taylor, city archivist

In the summer of 1604, Hull was experiencing another plague epidemic. In what must have been an atmosphere of panic and suspicion, many people thought that the infection could only be explained by black magic. We know this from a brief account in one of the Bench Books – the minute books of the town’s governing Bench of Aldermen.

In September 1604 a judge, Baron John Savile, arrived in Hull to hold a Session of Gaol Delivery, a trial of serious criminal cases. Baron Savile found that many (“divers”) people, men and women, were to be tried for witchcraft. Unfortunately, we don’t know any specifics of the cases, but it is likely that fear of the plague had prompted neighbour to turn on neighbour, and long festering disputes and resentments had broken out in wild accusations of witchcraft

Witchcraft was in everybody’s mind. The new King James I had arrived from Scotland the year before with experience and a morbid interest in witchcraft. A new law was about to come into force at Michaelmas (September 29) 1604 tightening up an existing law of 1563. Under both laws witches who were found guilty of harming people were to be put to death.

On September 4, Baron Savile found five men and women guilty of witchcraft: Roger Beadney; John Willerby; Mary Holland; Janet Wressell, alias Beamont; and Janet Butler. All five were sentenced to be hanged. The surnames of the witches were not Hull names but were to be found in the three parishes of Hullshire – Hessle, Ferriby and Kirkella – which came under the authority of the town. These people were outsiders, literally and figuratively.

Baron Savile is unlikely to have been a gullible man; he was intelligent, well educated, and a hugely experienced lawyer. But he may have had a point to prove to the new King – that the Common Law could deal with witchcraft – and he was also a committed Puritan, a group of Christians traditionally unsympathetic to accusations of witchcraft.

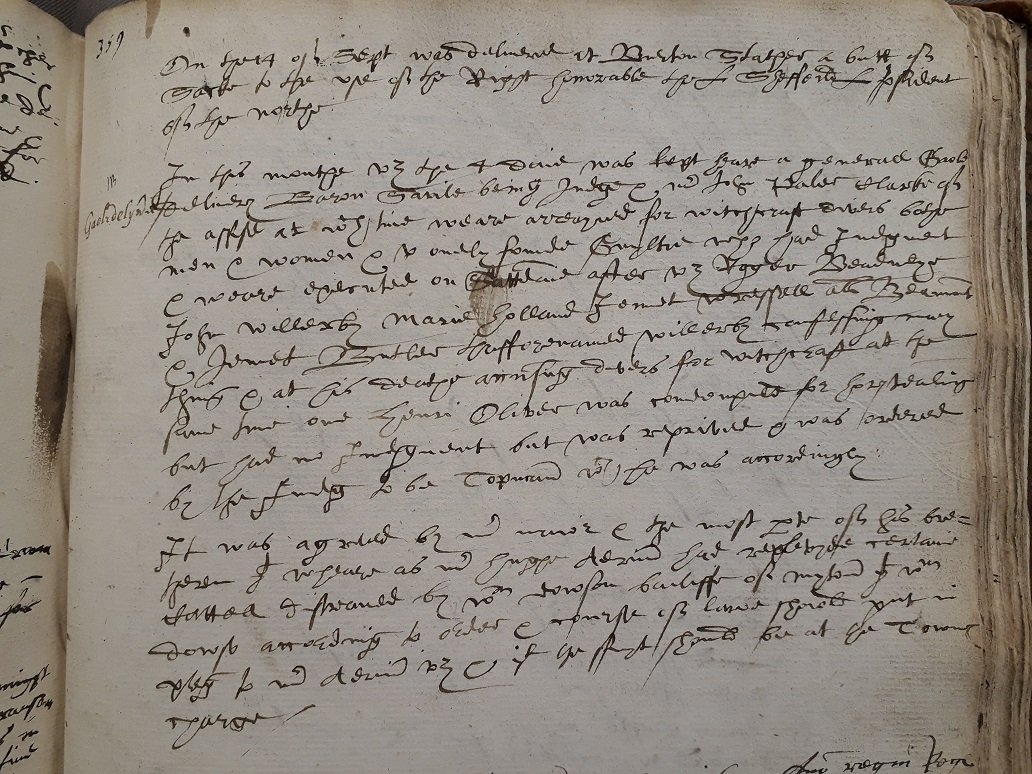

CASE RECORDS: An extract from the Bench Book of September 1604

So Beadney, Willerby, Holland, Wressell and Butler were hanged on Saturday, September 6, on the gallows where Adelaide Street now stands, then in the royal manor of Myton, where a field was once called Gallows Lane. Hull didn’t run to employing a fulltime hangman. According to the Bench Book, Baron Savile reprieved a horse thief, Henry Oliver, tried and convicted before him, on condition that he hang the witches. As a horse thief, Oliver will have known his way around ropes and halters.

Before Oliver’s noose went round his neck, John Willerby confessed “many

Thing[s] and at his deathe accus[ed] divers for witchcraft”. We can imagine the last desperate angry ranting of a man with nothing to lose, accusing former friends and neighbours in a scene reminiscent of The Crucible or The Name of the Rose.

We don’t know where the witches were buried. Soon after the trial, the Bench ordered various sanitary improvements which would have had a greater impact on the Hull’s public health than ridding it of witches. But that, we’re afraid, would not have been the view of most people in Hull in 1604.

Elizabeth Jackson of Rowley and the Salem Witch Trials, by Neil Chadwick, librarian and archivist

On the 19th of July 1692, five women were hanged in Salem, Massachusetts. Their conviction was one of witchcraft. One of the accused was Elizabeth Jackson, born in the hamlet of High Hunsley, just 12 miles from Hull.

Elizabeth was just aged one when she emigrated with her parents to North America in 1638. They sailed from Hull in the June on a ship chartered from London named ‘John’, arriving in Salem harbour in August of that year. The family settled down, establishing a home in the newly formed settlement of Rowley, Massachusetts, taking its name from Rowley in East Yorkshire. By the age of seven, Elizabeth was a maid in the house of Ezekiel Rogers, formerly minister of St. Peter’s Church, Rowley, East Yorkshire, who was the driving force behind the emigration of Rowley’s parishioners to North America, which included Elizabeth and her family.

Aged 21, Elizabeth married James Howe from the neighbouring town of Ipswich. Elizabeth and James had five children in total. Elizabeth seems to have developed a strong assertive character, no doubt because her husband, James, was blind. It has been suggested that because of this, Elizabeth may have played a more pivotal and dominant role in the community, perhaps proving unpopular in a male dominated society. Perhaps it was this strong and assertive character that singled out Elizabeth later?

Problems began for Elizabeth in 1682. A young girl of a local family began to have fits in which she accused Elizabeth of making her ill. The young girl, however, refused to name Elizabeth as a witch, but the damage was already done.

Elizabeth was refused admittance to the church at Ipswich, and with it her and her activities became more isolated, perhaps adding to the already aroused suspicion. Things died down but the issue of witchcraft resurfaced again in 1692, this time in the nearby town of Salem. The community at the time was experiencing difficulties with what appears to be a series of unfortunate and unexplainable events. It was at this time that people looked for scapegoats. The 17th century was no stranger to witchcraft hysteria. England and Europe had witnessed such hysteria earlier in the century, and it now spread to the colonies in North America.

NEVER TO RETURN: The last view of England for the parishioners of Rowley as they left for North America in 1638

The events at Salem centred upon an enslaved women called Tituba who hailed from Barbados. She regaled horrific stories to a group of girls, including the daughter of Reverend Samuel Parris, to which they believed themselves to have been bewitched. The girls developed uncontrollable screaming and spasms, and with it the girls named those who had allegedly bewitched them. The first was of course Tituba. Other names followed, including that of Elizabeth Jackson.

Elizabeth found herself incarcerated in Boston prison. She found support from her family, but also from Reverend Samuel Phillips, minister of the church in nearby Rowley. Phillips met with the young girls. The girls refused to name Elizabeth as a witch, despite the best efforts of others to prompt them to do so. Others offered testimonies on Elizabeth’s behalf, including neighbours who described her as a good Christian.

Elizabeth along with five other women, were tried in June 1692. The trial began with people demonstrating that they had been bewitched by Elizabeth. Elizabeth was said to have also appeared in various forms of spirits and spectres. Perhaps the biggest blow to Elizabeth, and indeed her family, came from her brother-in-law, John Howe. He accused Elizabeth of bewitching some of his cattle to death. Of course this was fabricated, but due to Elizabeth and James having no male children, John stood to gain if Elizabeth was out the picture with any property reverting to John and not Elizabeth on James’s death.

In all some 150 people were accused of being witches or involved in witchcraft. Some were found guilty while others confessed to avoid death. Elizabeth maintained her innocence, but to no avail. The trial concluded inevitably with the sentence of death by hanging. Elizabeth along with four other women were executed on 19th July, their bodies simply cast into holes at their place of execution. Elizabeth’s death did not bring about an end to witch-hunting in Salem. Four men and one woman were hanged on August 19 with further executions on September 19 and 22. Eventually the frenzy did subside. In 1710, legal proceedings were brought to verify Elizabeth’s innocence. The conviction was eventually quashed, and Elizabeth’s family received compensation.

The Salem Witch Trials have captured the imagination of writers and artists over the last three centuries. The American Playwright, Arthur Miller, wrote The Crucible (1953), which was eventually turned into a film in 1996, featuring Daniel Day-Lewis and Winona Ryder.

Today many people have heard of the Salem Witch Trials, but not many know that an East Yorkshire woman was one of those at the centre of this tragic and infamous 17th century witch-hunt.

Find out more

Worship Street

Hull

HU2 8BG

Tel: 01482 317500

Email: hullhistorycentre@hcandl.co.uk

X: @Hullhistorynews

Facebook: hullhistorycentre