Larkin100: ‘He anointed Hull, and that’s complicated’

Philip Larkin

This Place, a column by Vicky Foster

Larkin100: A review of this week’s centenary celebrations

On Tuesday evening I sat next to the Poet Laureate to eat dinner. We discussed the best way to cut into the pork crackling without it jumping off the plate (lever it against the ridged edge and press gently) and whether choosing mushrooms over the mackerel had been a mistake.

Also in the room were Imtiaz Dharker, Virginia Bottomley – Baroness Bottomley of Nettlestone and Chancellor of the University of Hull – Rosie Millard OBE, and Eddie Dawes, as well as councillors, professors, artists, archivists, businesspeople. After the pork, Sir Tom Courtenay shared stories and read poems while we waited for the ice-cream to thaw for dessert. It was a heady mix of people to be drawn into a hot room in Hull on a Tuesday evening, and maybe there is only one name that could have brought them: Philip Larkin, and his centenary celebrations.

It was the culmination of a busy day for Larkin100 and The Philip Larkin Society. It began for me by listening to the Radio 3 Breakfast Show, which Petroc Trelawney had opened with a pun on Larkin’s name, and which contained his poetry and references to his life and work. I reread some of the articles which had been published over the last couple of weeks about Larkin, in the New Statesman, The Guardian, The Times, UnHerd. Then I got myself ready to go and soundcheck at Hull Truck Theatre with The Broken Orchestra at lunchtime, before the performance we’d be doing in the afternoon.

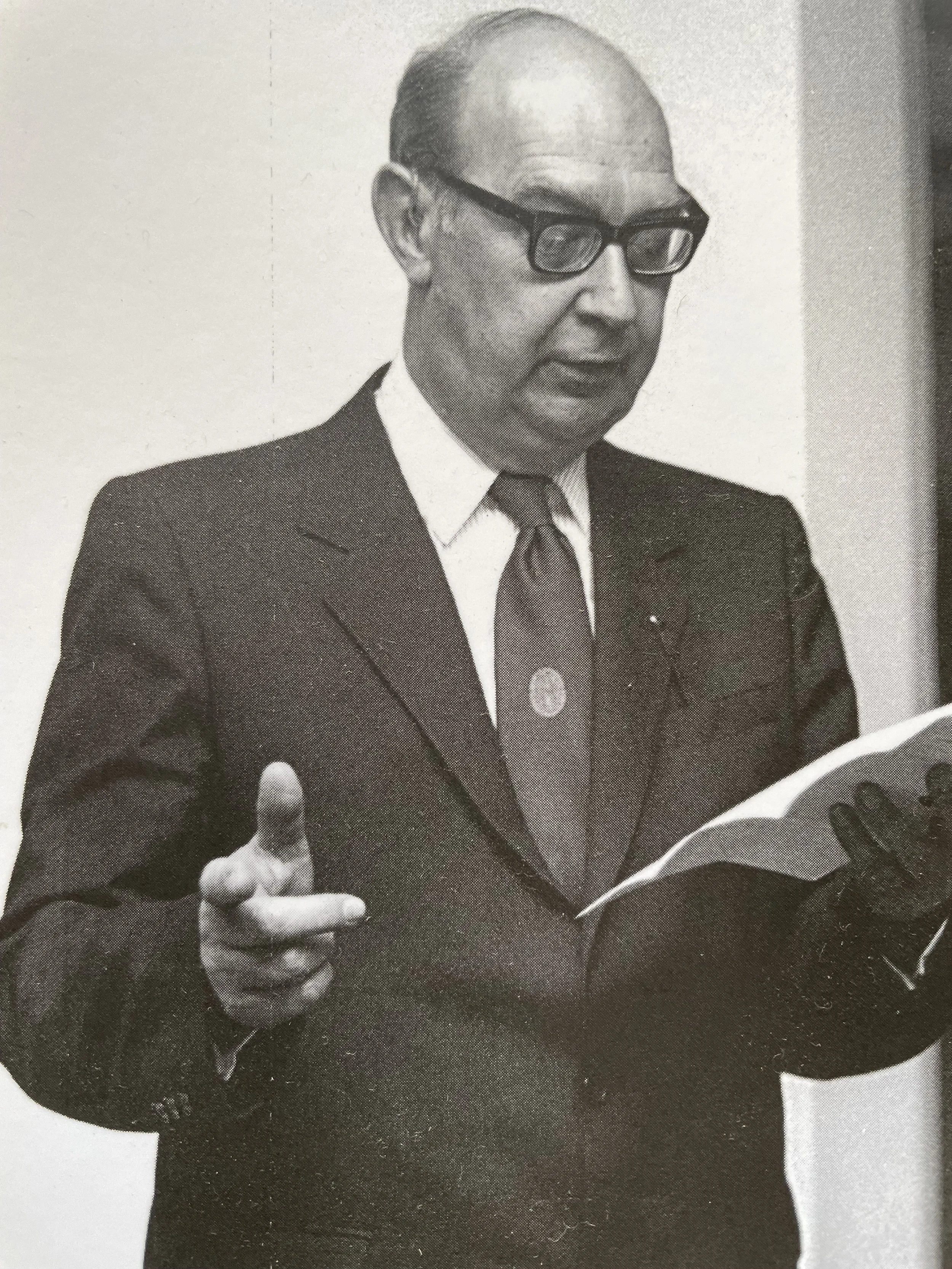

Poet Laureate Simon Armitage giving a reading for Larkin100 at Middleton Hall, University of Hull

I arrived to find Wes Finch and The Mechanicals rehearsing – double bass, guitar, drums, and vocals playing out into a still-empty auditorium – a gorgeous jazz mix of Larkin’s poetry set to music. Then JoinedUp Dance Company’s beautiful projections filled the space as they had a last-minute tech check. Over the next couple of hours, people and noise would begin to fill the theatre, but for now it was still peaceful.

Dharker was up in the roof garden giving an interview to Look North. Dr Matthew Sweet was double-checking his notes for his talks and introductions. I wandered into the lobby where I found Graham Chesters, fresh off the airwaves after talking on Radio Humberside about the day, and Philip Pullen. We grinned at each other. We were in the mood for celebrating, because this day had been a long time in the planning, and at times it had felt like the events, for which we were all now making last-minute preparations, might never happen.

So maybe it began for me back in November 2020, when I signed the official document that made me a Trustee of Larkin100, and myself, Philip and Graham began the long series of Zoom meetings, held in lockdowns and half-lockdowns, reopenings and sudden reclosures, where we tried to organise celebrations, whilst navigating concerns about not only whether events might be cancelled, but whether Larkin himself might be too. It’s been a bumpy two years. There’s been a lot to think about, and one of the things I thought about a lot before I signed that document was how I felt about Larkin.

Vicky Foster, left, with The Broken Orchestra at Hull Truck Theatre

So maybe it began for me back in the autumn of 1996, when I sat in a second-floor classroom at Wilberforce College and my A-Level English tutor handed out copies of The Whitsun Weddings. ‘Can you hear the rhythm of the train in the lines?’, my tutor asked. And yes, yes I could. But more than that – I could hear the way the train sounds would ring up against the high curved ceiling of the station, and off the hard floors. I could picture the train, setting out under the arched opening towards the Humber – ‘the river’s level drifting breadth’. I knew the place ‘Where sky and Lincolnshire and water meet’. I had never felt so close to an actual poet before. I had loved Hardy and Wordsworth and Shakespeare, and I had visited Stratford and Dorset and the Lakes, but I didn’t know them, not like I knew Hull. When the tutor explained that Larkin had lived here for the last thirty years of his life, until 1985, I felt a pang of loss. He had been so close, and now he was gone.

In a newly-commissioned poem, written for his centenary, Dharker imagined seeing Larkin on Tinder, and when I try to describe my relationship with him, I also find myself turning to social media. If I’d had to tick a box to define it on the Facebook of a few years ago, I would have chosen: It’s Complicated. In her article for The Guardian about the poem and the poet, Dharker says ‘Would I go up and speak to him? Never. Would he even see me? No, of course not, I would be nothing more than an unwelcome blot at the edge of his vision’. This is close to how I always imagine any interaction I might have had with Larkin. I have spent a lot of hours studying in his library, and he has always felt like a disapproving presence to me, peering out from behind the stacks and shaking his head. Has this stopped me from wanting to feel close to him? No. I once chose a house because I realised I could place my desk overlooking Pearson Park, and if it was good enough for Larkin, it was good enough for me.

‘BEAUTIFUL PROJECTIONS’: JoinedUp Dance Company performing at Hull Truck Theatre as part of the Larkin100 celebrations

But it’s more than that. If I’m honest I don’t think I really have a choice about whether I feel close to him. For me, he is indelibly marked on the city. How can you look at the river and not remember his ‘piled gold clouds’ and ‘shining gull-marked mud’? How can you drive the roads out towards the east coast without thinking about his ‘wind-muscled wheatfields’ and ‘unfenced existence’? This place feels somehow anointed by his words.

What, in my younger days, I might have described as a mucky brown river, is transformed, and so are the miles of barely inhabited, run-down roads and towns and villages. But that’s not all either. It feels to me that having had someone of Larkin’s calibre living and writing here gives others living here permission to write too. Suddenly, and this is what I now realise I felt when I first learned about him, 26 years ago; it’s not something that only happens in London, or rolling rural beauty-spots. It can be done here and can be just as appreciated.

Become a Patron of The Hull Story. For just £2.50 a month you can help support this independent journalism project dedicated to Hull. Find out more here

I was once at an event where Simon Armitage, the Poet Laureate, was talking to a group of schoolchildren. One of them raised their hand and asked if he was the ‘King Poet’. I didn’t hear how he answered, but I doubt anyone listening in Middleton Hall on Tuesday night would deny him that title. He read a blend of his own and Larkin’s poetry, woven with stories and observation, critical analysis, context, jokes. One of the things he said was that he’d recently realised how important Larkin might have been in informing the way he now writes. Tracing back an ancestry that included Hardy and Yeats, he spoke about Larkin’s accessibility and how a whole generation of new readers felt able to engage with his poetry.

But Armitage didn’t shy away from the darker side of Larkin – he also read Toads Revisited, describing it as Larkin at his cruellest, and it is a cruel poem. Larkin muses on the people you might meet in the park on weekdays: ‘All dodging the toad work, By being stupid or weak.’ I also take exception to the ‘cut-price crowd,’ ‘grim head-scarfed wives’ and ‘raw estates’ he describes in Here, because he could be talking about my family and their homes. But, as I discussed with Armitage when I met him during the making of his new Radio 4 series about Larkin, when he writes about the city in Bridge for the Living and barely mentions people at all, I miss them. Whatever his opinion of Hull’s people in his other poems, at least he includes them. My family are there alongside those other beautiful images, even if Larkin dismisses them so meanly.

‘A GORGEOUS JAZZ MIX OF LARKIN’S POETRY SET TO MUSIC’: Wes Finch and The Mechanicals

So, to come back to my earlier description of my relationship with Larkin: it’s complicated. Was he a perfect person? No. But in some ways that is also reassuring. The more I have learned about Larkin, the closer I have felt to him – a man who was uncomfortable in his own skin, who chafed against his day-to-day work, against petty jealousies, who lay in bed at night wondering ‘where can we live but days?’ Do I think I would have liked him in real-life? I don’t know.

On Tuesday night, tribute was paid to Graham Chesters for the work he has done over many years, setting up and running The Philip Larkin Society, and making sure it was located in, and continually associated with, Hull. I’ve been lucky enough to spend a lot of time over the last two years talking about Larkin with Graham – he has a wealth of stories and information and ideas to share, often surprising or funny. On Tuesday, before dinner, he gave a short speech in which he relayed Larkin’s reputed last words – I’m going to the inevitable – and also recounted the last words Larkin had spoken to him personally.

In that moment, something clarified for me: Larkin has always been an abstract, half-imagined figure in my mind, but for Graham Chesters and other people still living in Hull and elsewhere, Larkin was a friend, a colleague, a confidante, an acquaintance. He was a real person and real people are messy and complex and sometimes not very nice. Larkin shows us that despite this, they can still also be capable of great vision and great love. He celebrated that idea, stepping right inside it, turning his exceptional skill and discipline with words towards showing it to us. It’s all there in his poetry, spread out on the page, the difficult and unsightly sitting next to the transcendent, the beautiful. The mud is shining and gull-marked. The clouds are piled and golden. And we’ll keep celebrating that for the rest of this year. I’m proud to be a part of it.

The next Larkin100 events will take place as part of Freedom Festival, and further details of the rest of the programme will be announced in the coming weeks. The DJ Roberts exhibition Larkinworld 2 is currently on display in the Brynmoor Jones Library exhibition space, until September 25. You’ll be able to find details of all events as they are announced at: https://philiplarkin.com and on the Philip Larkin Society Twitter page: @PLSoc. The Simon Armitage Radio 4 series Larkin Revisited is currently being broadcast and all episodes will be available on the BBC Sounds webpage and app by Friday August 19.