The story of Sir John de Sutton and Bransholme Castle

HISTORIC SITE: Castle Hill, looking towards Sutton, 1875

The Way it Was

By Neil Chadwick, librarian and archivist at Hull History Centre

In 1352, Sir John de Sutton, Lord of Sutton, was charged for having built “a castle, crenelated and battlemented, at Bransholme, in which (the) castle, and houses are one and the same tenement”.

Today the site of Bransholme Castle is located by the Holderness Drain and is better known as “Castle Hill”.

The charges levelled against Sir John have often been cited as the earliest documented evidence of a castle at Bransholme. However, in the University of Hull archives at the Hull History Centre is a document that predates this. It is an account of lands held on behalf of the crown and refers to Branshomle Castle some 60 years earlier, in 1292.

Other than this, we know almost nothing of the castle. So, what is the story behind Bransholme Castle in the fourteenth century. We know the castle was built by Sir John, but why?

DOCUMENT: A translation of inquisition post-mortem after the death of Sir John

Sir John’s lordship is perhaps our best opportunity to understand more about Bransholme Castle. We not only get a description in the charges levelled against Sir John, but the time in which Sir John lived offers a clue to how and why a castle at Bransholme was built. To put it more precisely, The Hundred Years War and the newly developing town of Hull.

The year is 1346. England has been at war with its old foe France since 1337, better known as The Hundred Years War (116 years to be precise). In July 1346 Edward III crosses the channel with a huge army. The English defeat the French at Crecy in August 1346, arguably the most famous of all English victories against France during the campaign. Afterwards the English march on Calais, laying siege from September 1346 until July the following year.

Back in England, Sir John de Sutton is making his way to France. The Scots had just been defeated at the Battle of Nevilles Cross in September 1346. With the Scots defeated, Edward III called on his northern army to descend on Calais. Arriving at Calais in early November of 1346, Sir John remains with the English army throughout most, if not the entire siege. Calais surrenders in July 1347. After a gruelling siege, the English enter Calais victorious. Edward doesn’t let his army hold back. Also being the centre of piracy in the Channel at this time, rich pickings were to be had and Calais was stripped of everything.

EVIDENCE: A mandate for foreign merchants to sell their goods on the town of Hull during the period of truce with France

The early decades of The Hundred Years War proved fruitful for the English. Riches and money were to be had from the blood of French peasants with one or two nobles thrown in for good measure. Sir John reaped the rewards from the siege of Calais and its aftermath. Having stuffed one or two things in his trouser leg and under his helmet, Sir John was presented with property in Calais by Edward III. In May 1347 he was granted letters of protection from Edward for his good service, and therefore must have been held in high regard by King Edward himself.

Having returned home victorious from France, what would Sir John do with newly acquired wealth, political and social status? Today we’d perhaps buy a Porsche, Lamborghini, or Ferrari. Even a plush new pad. A fourteenth century knight like Sir John would look to build, extend, or make improvements to the family home. In his case, the family castle at Bransholme. And of course, being a good religious and pious man, perhaps wanting to atone for all the bloodshed in France, he rebuilds large parts of the church at Sutton.

Now aged 40, old by medieval standards, Sir John could have been forgiven if he’d simply put his feet up, raised a flag above his castle and settled back, glass of wine in hand enjoying the fruits of his labour. Sir John, however, appears to have inherited some of that Sutton family feistiness, probably from his great-great grandfather Sayer II, who was a rather nasty individual. Sir John had a grudge, a grudge that went back to the time of his father’s lordship. This grudge was directed at the newly founded town of Hull. And for Sir John, it was personal.

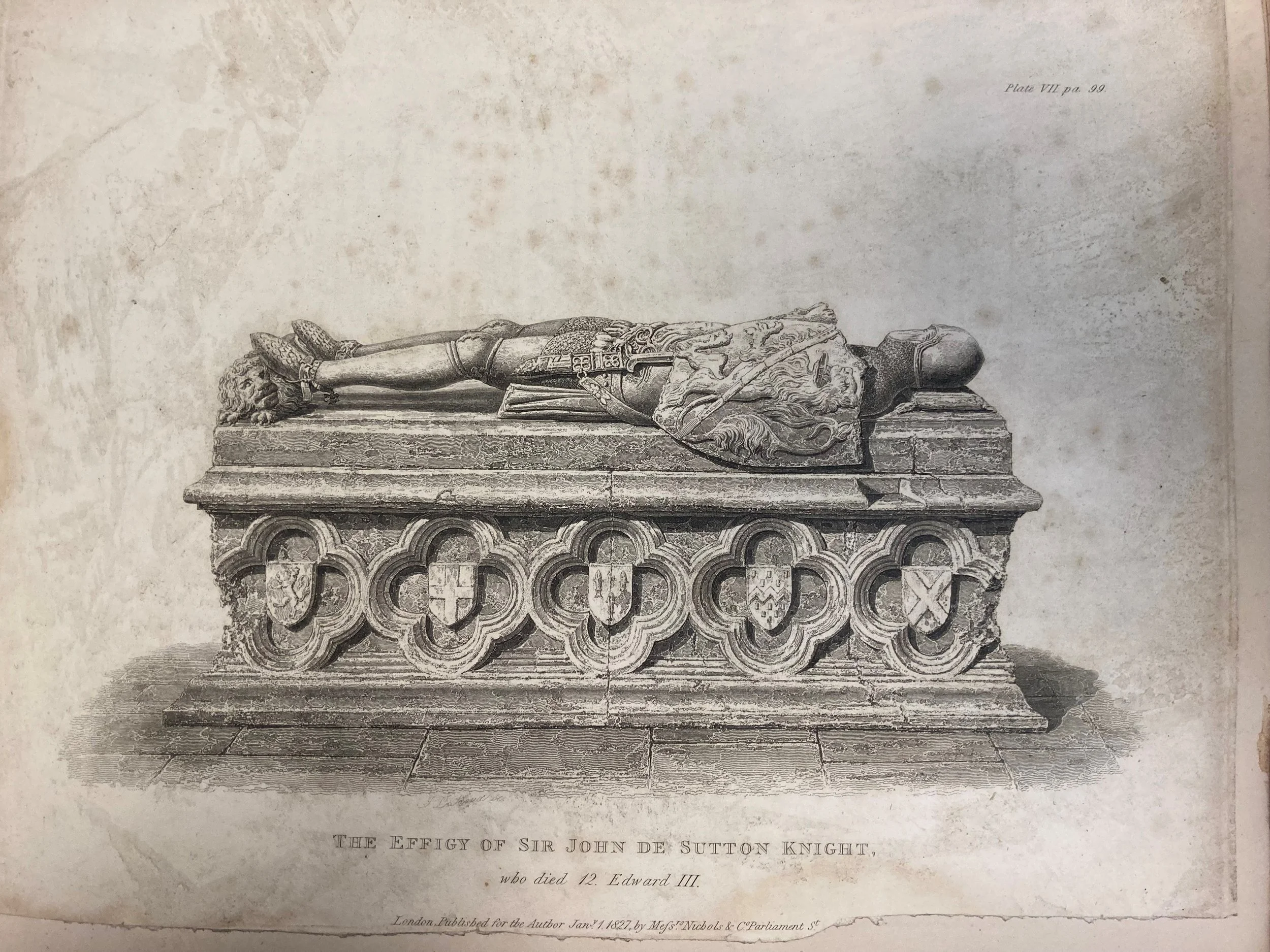

EFFIGY: Sir John de Sutton’s tomb in St James Church

From the mid-thirteenth century, the old River Hull began to silt up. A new outflow emerged by what is now the River Hull’s confluence with the Humber, by The Deep. This inlet or creek, then known as Sayer Creek, was used to drain Sutton lands on the eastern side and named after Sir John’s great grandfather, Sayer III. It was Sayer III who had granted the nuns of the Priory of Swine access from Bilton to Drypool through Sutton lands at Southcoates. Today the route is better known as Holderness Road. The Sutton family also had a ferry at Drypool which crossed Sayer Creek, and later the newly established course of the River Hull. With the monopoly over the river crossing south of Stoneferry, the Sutton family was on to a nice little money earner.

However, these rights and holdings were taken. Upon acquiring the town of Hull, Edward I set about on creating economic prosperity. Losing the rights to their ferry crossing, Edward had denied the Sutton family one of its means of income. And it didn’t end there. The Holderness Road was taken by the crown and became the Kings Highway to the east. And to rub salt into the wounds, Sayer Creek, now the outflow of the river Hull into the Humber was full of ships transporting wool abroad and bringing goods such as timber and wine from the continent.

Sir John’s father, Sir John the Elder, petitions the King over the next 30 years or so, but fails to regain control or obtain compensation. Sir John the Elder dies in 1337 and into his shoes steps his son, Sir John. Sir John now saw the opportunity to antagonise the situation. However, Sir John was simply a minor lord. It’s one thing taking on people less powerful than him, but taking on the newly developing economic powerhouse that is Hull, backed by the crown, was another matter altogether.

MAP: Course of the old River Hull known as ‘Aulde Hull’ and Sayer Creek

Alert to the world around him, Sir John sees an opportunity in France to make a few quid, perhaps gain some political influence and social status among his peers. Perhaps he can return home and mount a serious challenge to win back previous Sutton rights and possessions. Despite Sir John’s success in France financially, politically and socially, regaining his family’s possessions and rights was wishful thinking. The best Sir John could do was to poke the beast. And one way to achieve this was to build a castle.

Fourteenth century castle building had moved on drastically since the Norman Conquest. Gunpowder, introduced into Europe by the beginning of the century, now made it easier to breach castle walls. Castles were now more to do with status than necessarily structures of defence.

That said, walls still provided a form of resistance. After all, Hull’s town walls continued to be built during the fourteenth century. Rounded towers, some of which were incorporated into Hull’s defences, were designed to deflect cannon shot, whilst arrow and gun loops, seen as decorative features, if placed carefully, could ensure all lines of fire were covered. And of course, battlements could easily hide an archer or crossbowmen. In the wrong hands a castle could still pose a threat. And Sir John knew this.

DOMINATING THE SKYLINE: How Bransholme Castle may have looked in the marshes of Holderness during Sir John’s lordship in the 14th century

When Sir John was charged for having built a castle, we do not know where he and the justices met to thrash things out. Perhaps Sir John invited them to his new castle, greeting them to a slap-up meal, free bar, complete with entertainment. Had this not impressed his guests or softened their stance, he may have offered them a brown envelope (or medieval equivalent) together with a wink to seal the deal.

This failed. Things may have got heated. It did not go as far as drawing swords or deciding the dispute on a duel or a fight to the death. And whilst Sir John must have initially stood his ground, he knew his stance would be in vain. He may have pulled the old chestnut, insisting he’d built it to protect the realm from the French. He did however insist he built it to protect the town of Hull from the Kings enemies. Despite this, Sir John reverted to plan B. He asked for a pardon and paid a fine of 20 shillings. In return, Edward III pardoned him and granted Sir John a licence to crenelate.

Sir John got to enjoy is castle for just five years. He died in 1357. The castle passed to Sir John’s brother, Thomas. Thomas died without a male heir and the castle passed to his eldest daughter, Constance. She married Peter de Mauley, but it appears by this point Bransholme Castle was resigned to history.

Find out more

Worship Street

Hull

HU2 8BG

Tel: 01482 317500

Email: hullhistorycentre@hcandl.co.uk

X: @Hullhistorynews

Facebook: hullhistorycentre